Bhima swarga

[quote]Kertha Gosa means - “the place where the king meets with his ministries to discuss questions of justice.”

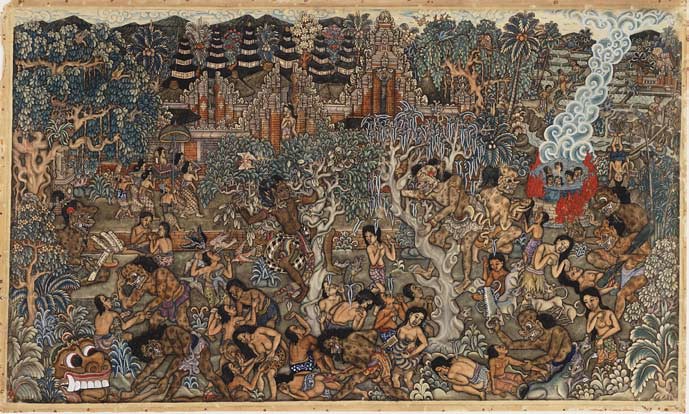

The story of Bhima Swarga is elaborate and all-embracing. Bhima Swarga in Balinese means, “Bhima goes to the abode of the gods.” Swarga literally means to any place where the gods happen to reside, Heaven or Hell.

Bhima, the second oldest of the five Pandava brothers, is forced by his mother Kunti with the mission to rescue from Hell the souls of his earthly father Pandu, and his second mother, Madri. After saving Pandu and Madri from Hell, Bhima must secure them for Heaven. Throughout Bhima’s journey to Heaven and Hell he is accompanied by his two loyal servants (the clown characters). These made up characters are highly important to the story Bhima Swarga because the ordinary Balinese can relate to the characters in the story Bhima Swarga because the characters represent ordinary Bali.

Bhima’s siblings go through hell right along with Bhima to rescue their parents. The siblings observe people being tortured for their sins. The siblings are Arjuna, Nakula, Sahadewa, Yudhishthira, and Bhima. The two clown characters whom accompany Bhima on his journey to Hell are Twalen and Mredah. Twalen wears a black checkered loin cloth and is the helper to Bhima. Twalen translates what is being said by Yudhishthira and Kunti. Mredah always wears red checkered loin cloths and he also helps Bhima along with cracking a joke to lighten the mood. Bhima goes to Hell to rescue his parents and when he arrives he finds his parents are in a huge hot water bath. Bhima tips the bath which his parents were boiling in and they are taken off to Heaven. The Demons did not like Bhima rescuing his parents and allowing them to go to Heaven. Bhima then has to fight off the Demons. Next, the Gods do not like this idea of Bhima taking his parents from Hell to Heaven. Bhima then gets into a fight with the Gods and Bhima dies in Heaven. The high God of all restores Bhima back to life and gives Bhima the drink of immortality. The last scene of Bhima Swarga shows justice, even with punishments of Hell.

The ceiling of Kertha Gosa is painted in a traditional Balinese style that resembles wayang, “shadow figure”. Paintings in the wayang style are related closely to shadow theatre art, relating to the Mahabharata and Ramayana stories. Wayang style paintings have been faithfully preserved that it continues today to reflect Bali’s Hindu-Javanese heritage in its traditional iconography and content. Iconography was used a lot in Bali’s culture. Iconoclasm is used because the Balinese people wanted to represent living things through pictures and shadows; it was prohibited to represent any living entity. [unquote]

Bhima Swarga: The Balinese Journey of the Soul: Pucci, Idanna

Halus (Delicate) and Kasar (Rough) Characters in a Scene from Bhima Swarga

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kertha_Gosa_Pavilion

Stutterheim W.F. (1956) An Ancient Javanese Bhima Cult. In: Studies in Indonesian Archaeology. Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Springer, Dordrecht

Abstract

To lesser known products of the final period of ancient Javanese art belong statues of Bhima. Of these only a few are known, but others are easily recognizable as such. I hope shortly to review the principal examples of these statues, which as yet have failed to find their place in the official art history of Java, mainly because no one has known where to place them. They fitted in poorly ; they are neither gods nor the usual type of temple guards, and the existence of a special Bhima cult is unknown. Furthermore, why only Bhima and never the popular Arjuna? For this reason one would search for them in vain in the standard works on ancient Java, and were it not that Bali put me on the trail of their probable significance I would have gladly resigned myself to this situation. Now, however, I believe I am in a position to cast further light on these statues and, unless I am greatly mistaken, even to associate their worship with various traces which can be found today. To this end there follows first a cursory survey of these statues, which it was hitherto impossible to fit in, but which, as I hope to show, are in fact to be considered coherent, valuable data from Java’s past.

References

- 1).OR, 1913, p. 281.Google Scholar

- 2).OR, 1910, p. 115.Google Scholar

- 3).TBG, LXII (1923), p. 502. I suspect that the meaning of the sĕngkalan is related to the representation of the figure. In that case, however, the meaning of the term “Bima gana rama ratu” is not clear to me; I think it not impossible that “rama ratu” refers to Bhima’s father, Pāndu.Google Scholar

- 4).Yet Knebel must be read critically. In speaking of the Javanese physiognomy, he refers exclusively to the Bima of the Javanese wayang and not to the Javanese themselves. It would be more accurate to say that it is completely un-Javanese, at least certainly not mid-Javanese. He also speaks of an inscription on the back panel; this should be “on an ornamental piece in the form of a double wajra-club placed against the back panel.” The following should be noted about our reproduction. The figure has been subjected to rather extensive restoration; the polèng pattern has been accentuated by color and, in accordance with the wayang tradition of the post-Kartasura period, trousers have been painted on the originally bare thighs.Google Scholar

- 5).Catalogus Groeneveldt, no. 286 6 (photograph O.D. 931). Figure no. 310 d (photograph OD 932) possibly also portrays Bhima, but then in another episode. As is known portrayals of Bhima are also found in the wayang. These vary slightly from one another, each depicting a certain period in his life. The same is true of Arjuna and a few other heroes often appearing in the plays.Google Scholar

- 6).Hoepermans speaks of figures “from a wayang play” (OR, 1913, p. 287). Knebel did not make the trip (OR, 1910, p. 114). Among the figures shown in the photographs of the excavation, some can be recognized as Bhima because of snakes, moustache, panchanaka and polèng. The antiquities of Sukuh are located at a height of 910 m., those of Chĕta at an altitude of 1470 m.Google Scholar

- 7).OR, 1913, p. 322. The antiquities of Pĕnampihan are situated at an altitude of 897 m.Google Scholar

- 8).OR, 1908, p. 203.Google Scholar

- 9).In character this figure closely corresponds to the Bhima statue of unknown origin in the Museum at Leiden (Cstalogus Juynboll, V, p. 29, described under no. 1861 as “temple guard or rākṣasa”) (Fig. 8). It is undoubtedly again a Bhima.Google Scholar

- 10).Knebel (O.R., 1908, p. 153) fails to mention the piece, which suggests the possibility that is was brought there later. Krom mentions the figure in Inleiding, II, p. 157 (“figure with so-called wayang hairdress”).Google Scholar

- 11).OR, 1902, p. 302. Pagersari is located at an altitude of about 900 m.Google Scholar

- 12).As is known, in the wayang, the type is primary; the person portrayed, secondary. Therefore it would be possible, if desired, to play several lakons with one set of dolls, each of one of the established types. It is true that in the expensive and over-complete wayang sets of the courts and dalĕms a distinction is also made between the puppets, but this is not really necessary for the play. If necessary, the same puppet can be used, e.g., for Brama and Baladéwa, as is commonly done on Bali. This is even the rule in masked plays (topèng).Google Scholar

- 13).OR, 1904, p. 102. Knebel failed to notice the twenty-one-line inscription on the back and sides in careless Sukuh script. Although for this reason not mentioned in the Inventaris, the inscription appears to have been recorded later at the Archaeological Service; there is a rough copy which I have not yet been able to decipher.Google Scholar

- 14).Bima is associated with the origin of the Serayu (see p. 48) and with the legendary pit, Jala Tuṇḍa, which gives entrance to the underworld. The largest of the still remaining chaṇḍis is called Bima (see Djåwå, 1925, pp. ff).Google Scholar

- 15).OR, 1908, pp. 223, 227. A similar figure was also be found at Trĕnggalek (OR, 1915, Inventaris, II, no. 2014). At present the figure of Sunggangri stands on the market place.Google Scholar

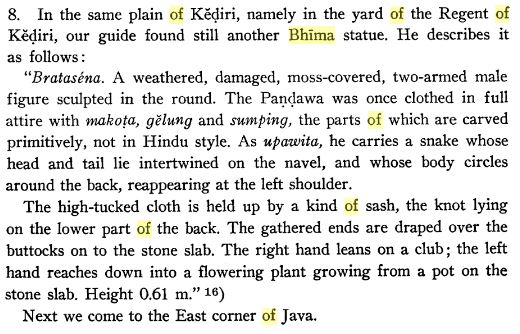

- 16).OR, 1908, p. 237. Kĕḍiri is the “tâche noire” on the archaeological conscience. In 1866 on the occasion of a visit by the Governor-General Sloet van de Beele, Resident Officer Van der Kaa gave orders to carry all loose figures in the vicinity to Kĕḍiri. This was done, however, without taking adequate note of their location. Nearly 200 figures were involved. In fact the Governor-General (according to Hoepermans) asked whether the Resident meant to use these figures as “in a showcase”.Google Scholar

- 17).OR, 1904, p. 99. Wana-asèh is located near Prabalingga.Google Scholar

- 18).OR, 1904, p. 147. The statue is now found in front of the Assistant Resident Officer’s house. It is not clear to me why Knebel calls numbers 8 and 10 Brataséna and the remainder Bima or Wĕrkodara. Brataséna is the youthful Bima’s name and is represented in the wayang by a separate puppet (with hair hanging loosely, see fig. 22); this distinction, however, does not appear from Knebel’s description.Google Scholar

- 19).Oudheden van Bali, I, pp. 160 ff.; OV, 1925, p. 158, No. 17a. The above description of the figure is somewhat more detailed and contains a few corrections. In connection with the correction in the name made by Chatterji in Modern Review, February, 1931, — which I gladly follow — I must note that on the basis of van der Tuuk, KBNW, I, sub voce catur, we must assume that, had the combination catur and kāya been made in Java, the sandhi rules would not have been followed, and the term caiurkāya which I suggested would have resulted. The well known caturmukha would have been followed. Nevertheless, since a scientific classification and not an ancient Javanese name is involved, the above correction is right, in my opinion.Google Scholar

- 20).Oudheden van Bali, I, pp. 184 ff; Fig. 85.Google Scholar

- 21).Oudheden van Bali, I, p. 164; II, Fig. 50.Google Scholar

- 22).Oudheden van Bali, I, p. 165; II, Figs. 53, 54.Google Scholar

- 23).The original style of wearing the hair knot at the side of the head is still in frequent use with Balinese women.Google Scholar

- 24).Brahmāṇḍapurāṇa, Gonda ed., p. 56: 13 ff. See also van der Tuuk, KBNW, sub voce aṣṭasañjña. (1: 213b).Google Scholar

- 25).I suspected a connection with the Bhairawa cult of Singasari in Oud-heden van Bali, I, p. 166: “Beyond a doubt we are faced here with a Baliniese variant of the magic sanctuaries of Singasari whose kālacakra meaning was first clearly brought to light by Moens. Undoubtedly the Balinese pendant is cruder, but also more fantastic and impressive, although with the little which remains of this. glorious past we are no longer able to sense as keenly the true impression on the receptive and tender mind of the Balinese which such figures must have made in a moonlit, moving Indian night of magic festivities.” And p. 168: “However the meaning of the corpse-like figure on which the image stands is also none too clear. While we can point to similar forms in Tibet and India where they fill an important part in the conceptual world of the Buddhists, these areas are too far removed to serve as examples without modification. For that reason I prefer once more to point to the Singasari temple which apparently was associated with the initiation of members into a certain secret sect. This initiation undoubtedly was again related to the lingga cult as a means of strengthening and preserving the royal authority and the power of the ruling dynasty, which in turn was closely related to productivity in the realm and prosperity in general. Here we are faced with a set of customs and ideas which will yield its secret only extremely slowly, and here, too, Bali can once more provide important material for further detailed studies.” For the kāla symbol of the mask see ibid. pp. 166 ff. Fortunately it is now possible to supplement and correct this material.Google Scholar

- 26).Nevertheless, the Bhairawa form is also scarce; Java has only a few, Sumatra only one.Google Scholar

- 27).It now appears from an article about chaṇḍi B at Singasari in TBG, 1934, Nos. 3 and 4, that the Bhairawa has been wrongly associated with Kṛtana-gara and tower temple. There are reasons to believe that this cult first arose or flourished in Çiwaitic form under Sumatran influence during the heyday of Majapahit.Google Scholar

- 28).TBG, LXIV (1925), plate opposite pp. 556, 557.Google Scholar

- 29).In this connection I wish to draw attention to the fact that during a sacrificial ceremony in the pura Kĕbo Edan (= “crazy bull”), where the Balinese Bhairawa figure described above is located, I observed cloths with polèng pattern instead of the customary white cloths.Google Scholar

- 30).Thus still in the reliefs of Sukuh. BKl, 1930, p. 566.Google Scholar

- 31).See Gids voor de Oudheden van Soekoeh en Tjĕṭa (Soerakarta, 1930) and Oudh. Aant. XIII, XIV (BKI, 1930).Google Scholar

- 32).For the Bhairawa sects, see in addition to Moens, loc. cit., Goris in Oud-Javaansche en Balineesche Theologie, s.v. ; Pigeaud, Tantu Panggĕlaram, s.v. ; and most recently Goris in Mededeelingen der Kirtya Liefrinck van der Tuuk, No. 3, pp. 42 ff. The Bhairawas were pre-eminently the sect of forbidden things. It was believed that, by a ritual performance of that which was forbidden to the normal mortal or in which he was restricted, soul and matter could be divorced and the former could be absorbed into the deity, if possible during life. Ritual orgies with excessive indulgence in the five forbidden things (māngsa — meat, matsya — fish; madya — alcohol; maithuna — intercourse [in the sense of promiscuity] and mudrā — according to some, mystic gestures, according to others, grain) served as rites of deliverance. The symbols indicate death and horror (offering knife, skull bowls, etc.) or erotism. Furthermore, the divoree between soul and matter obtained by their observance produced supernatural powers which effected miracles (flying through the air, invulnerability, etc.) and made their sect a truly magic sect. At this point witchcraft and black magic enter; these form a popular edition of what was originally meant as ritual and worship. The native shamanism essential to ancestor worship, with its trance dances, etc., provided a welcome breeding ground for these foreign sects. Much of the demonic character of the popular religion in Bali is, in my opinion, due to this. Elsewhere I hope to trace the connection between this Balinese demon (léyak) faith and “Bhairawism” ; here I merely want to point out that in one of the léyak magic formulas, set forth by De Kat Angelino in TBG, LX (1921), the léyak praying for magic power considers himself a representative of Bima sakti and emissary of Batara Bayu. This undoubtedly points to a connection between the léyak faith and the figure of Bima-Bhairawa. It is, however, not clear to me whether the mantraBhimaçakti (has this anything to do with the Bhimas-tawa?) or the well known dark spot in the Milky Way is meant here.Google Scholar

- 33).See Cohen Stuart, Bråtå Joedå, I: XII, note 22; and Kats, De Wajang Poerwå, pp. 254 sqq.Google Scholar

- 34).Juynboll, Supplement Catalogus etc, I, p. 267, No. DCCXI (Cod. 4132) “Bhïmaswarga. Contents : Paṇḍu goes to hell for having killed the holy Kindama — a story derived from the Adiparwa. His widow Kuṇṭi urges her five sons, the Pāṇḍawas, to liberate their father from the kawah. In this undertaking Bhima supports his mother and brothers. The clowns, Dilĕm, Twalèn and Sangut, the Balinese equivalents of the Javanese Sĕmar and his sons, Pétruk, Nalagarèng, etc., also accompany him. Bhima fights Chikrabala, Gora Wikrama, Utpata, Jogor Manik and Suratma, the dorakālas and the hellhound (asu gaplong), until he finally obtains Pandu’s ātman.” (It is not clear to me what Dilĕm and Sangut are doing in the company of Twalèn — and this without the presence of the latter’s colleague Mĕrdah. The former are the parĕkm Korawa, the latter those of the Pĕndawa. Dilĕm, Twalèn and Sangut are in no event camparable as a “set” to Sĕmar, Pétruk and Nalagarèng). See also the Rama nitis (ibid. II, p. 75, infra). Stanza III of the same poem attributes another liberation to Bhima, viz. that of Dharmawangça (Yudhiṣṭhira).Google Scholar

- 35).Gids etc. p. 24; photo O.D. 7126.Google Scholar

- 36).These antefixes are also found on the main monument of Sukuh.Google Scholar

- 37).Here we have again a picture of the rainbow whose probable Austronesian origin was recently revealed by Bosch (BEFEO, XXXI, pp. 485 ff). The exact meaning of this rainbow is still not clear, although it is now evident from everything that it appears over magically powerful persons and at magically important events. This is, however, a far from regular pattern.Google Scholar

- 38).See H. E. Mangkunagara the VIIth, in Djåwå, 1933, pp. 79 ff., especially pp. 92 ff. Significant is the connection laid between lakon and sĕmadi, samādhi in Indian yoga is the higher stage of meditation (dhyāna) which aims at salvation.Google Scholar

- 39).See Vreede, Catalogus, etc., p. 248, No. CXLVII (Cod. 1804), the contents of which are quoted by Goris in Djåwå, 1927, pp. 110 ff. Also Berg, Inleiding tot de studie van het Oud-Javaansch, pp. 107 ff.Google Scholar

- 40).Goris, Storm-Kind en Geestes Zoon, Djåwå, 1927, pp. 10 ff.Google Scholar

- 41).Goris gives Gandamayit as the name of a cemetery where Bima was buried (Djåwå, 1927, p. 110). Elsewhere, however, I found Gandamayi and Gaṇḍamayu, which must nevertheless be names of cemeteries, in view of the Balinese name of the cemetery (sétra) Gaṇḍamayu: in the Calon-arang legend the witch of that name appeared at this spot before Durga (De Kat Angelino, TBG, XL, 1921, p. 10).Google Scholar

- 42).On the first occasion while drunk he is thrown in the well Jalatuṇḍå by the Korawa; on the second he acts drunk in the episode of the lacquer house. The original significance of the statement in the rĕrĕnggan about his “evasion of the five evil passions” also appears to me to have been censored (Goris, Djåwå, 1927, p. 111), especially as it is related to the five-colored polèng, which we encountered again with Bhairawa. Originally the meaning was probably that he exercised the five passions (the five rituals mentioned above?) ritually, which has to be camouflaged for the general public. Cf. the lakon Pĕjahipun Dursascma, in which Bima drinks the blood from the corpse of his enemy. I wish to draw attention, superfluously perhaps, to the demonic features in the physiognomy of the Bhīma of the reliefs and of the Bima puppet in the wayang, which differentiate it entirely from that of his brothers (round eyes, protruding nose, knots above the nose, etc.).Google Scholar

- 43).After what has been said above I would not be surprised if Bhīma had also been associated in some manner to Buddhist schools of deliverance; in the matter of deliverance practices, the distinction in Java between Çiwaism and Buddhism was extremely narrow. From a perusal of a translation of the Dewaruci (Middle Javanese tembang, Ms. Bg. No. 279) received from Dr. Poerbatjaraka, I found that Bhīma’s teacher Dewaruci is there described in the following terms: jtnarsi, buddhatatwarṣi, janārdana, ādibuddharṣi, and finally, werocana! Inasmuch as Dr. Bosch has informed me that he plans to publish some further particulars in this connection, I refer the reader to this publication. [See India Antiqua, pp. 57–62].Google Scholar

- 44).It is to be noted that the only bronze skull vessel was found on a mountain slope (Djåwå, 1929, pp. 14 ff.). In the Punjab, the Bhairawas were publicly known as kapālikas, i.e. skullers.Google Scholar

- 45).One may well wonder about the influence of Wāyu who, after all, is considered the corporal father of Bhīma and who gave him as a brother Hanumat. In my opinion, however, not too much importance is to be attached to that paternity in the popular representations in Java; in the Archipelago Wāyu has even been eliminated as father of Hanumat by the representation that the latter in reality was the son of Rāma and Añjanā and that Wāyu merely acted as intermediary (See Ramalegenden und Ramareliefs in Indonesien, I, pp. 94 ff.). Winternitz further points out that the episode in which Wāyu functions as the father of Bhīma cannot belong to the core of the Mahābhārata (Geschichte der Indischen Literatur, I (1909), p. 276). From the examination of the Rāma stories cited above we know furthermore that in the Archipelago we may expect earlier rather than later official versions of the Hindu epics. For these and other reasons I am constrained to consider Wāyu in the popular representations in this connection as being of secondary importance, however much his paternity of Bhīma may have been highlighted under the influence of the kāwya literature, which was current among the kakawin in Java. In any event, I would not attach such a great importance to his paternity as to explain all of Bima’s nlystic characteristics as being derived from him, even though I quite agree with Goris that the association of Wāyu = windgod with Wāyu = breath, spirit of life, must have had a considerable influence on the Bima mysticism. It is a fact, however, that in the Bima writings our hero has been associated with Guru = Çiwa, but not with Wāyu. There, Déwaruci “reveals” to Bima that he really descends from Batara Guru: perhaps we must interpret this as an intentional correction of the Wāyu legend. (In passing I wish to observe that the identification of Nawaruci (Déwaruci) with Çiwa, made by Berg in his Inleiding, p. 109, footnote 2, is not so obvious to me. Nawaruci is the Acintya, the “not-being”, in my opinion the portrayal of a philosophical concept. In present-day Balinese art it is represented as a small creature, sexless, with strong, magic colorings, formed from personified mantras. This creature is never associated with Çiwa. Çiwa is much inferior to the Acintya, as this wondrous unreal character is called. In my opinion it is undoubtedly this creature that is meant by Nawaruci, not a god, there fore, but the personified, mystic mythic-philosophical, highest attainable perfection, the hakīkah, or if one prefers, the nirwāṇa. Compare the above passages from the Déwaruci, where he (== Nawaruci) is called Wai-rocana, who also rates higher than Çiwa.Google Scholar

- 48).I wish to express my gratitude to H. E. Mangkunagara VII for the extracts from the lakons Bima bungkus and Paṇḍu swarga in Appendices I and II. They are lakons from Surakarta.Google Scholar

- 47).= Dhṛtarāṣṭra, the blind brother of Pāṇḍu.Google Scholar

- 48).= Çakuni.Google Scholar

- 49).= Duryodhana, in the lakons also called Duryodana.Google Scholar

- 50).= Childhood name of Arjuna. Elsewhere Pĕrmadi. Elsewhere, again, Janaka.Google Scholar

- 51).This may well be interpreted as “asceticism in order to obtain supernatural powers for the coming battle.” Thus, apparently do the Korawa consider Bima’s stay in the caul, whereupon they are advised to do likewise so that they will not fall behind the Pĕṇḍawas in “kasaktèn”. Scene VIII accordingly relates that nature became disturbed (read: the magic balance was upset) by Bima’s stay in the caul.Google Scholar

- 52).The original form is, presumably, Gandamayi from the Sanskrit gan-dhamayi, “consisting of odors”. From this Gaṇḍamayu have been derived.Google Scholar

- 53).= Gāndhāri, the “princess from Gandhāra.”Google Scholar

- 54).= Duhçala.Google Scholar

- 55).Note the beginning which is stereotypical of almost every lakon, the first scene showing the king in council seated in the state pĕṇḍapa in the innermost of the kraton, the second scene letting him go “inside” to go to his wives, and the third leading the spectator “outside” by having the governor and general transmit the king’s commands to the troups assembled on the alun-alun.Google Scholar

- 56).Most names of buta-kings start with Kala-, but often cannot be traced to the Sanskrit original, the ḍalang usually having taken greater liberties with respect to them than with respect to the Pāṇḍawa and Kaurawa. From the liberties taken even at present with the lakon by the ḍalang — especially from the kraton — it may be readily assumed that the old names were changed in order to make an allusion to persons who were not too highly thought of. Even today figures cherished by the king are given prominence; others are used to make subtle allusions, disparaging or complimentary, to persons or events. In the event that the king enjoys seeing two figures which date from entirely different periods, no scruples are felt about violating historical legend and creating a so-called charangan lakon in which both figures appear on the scene simultaneously. A similar motivation probably gave rise to the creation of the Rama nitis (Catalogus Juynboll, II, p. 74).Google Scholar

- 57).Elsewhere, Baturĕtna, “jewel stone”.Google Scholar

- 58).Buta kings usually have female patih’s, governors. Kĕpĕt is a kipas, fan; the origin and meaning of the name escape me.Google Scholar

- 59).Is this a hidden trace of fraternal marriage? As I have to demonstrate elsewhere, very ancient traits may be expected particularly in the lakons; the above swaya?wara is very unusual indeed.Google Scholar

- 60).Normally, one would expect the gara-gara somewhat later, so as to begin exactly at twelve o’clock.Google Scholar

- 61).Ganeça. Sang Hyang Pramèṣṭi (= paramesthi) Guru is therefore Çiwa.Google Scholar

- 62).Version B of the lakon (see infra) shows the relation between Uma and Gajahséna.Google Scholar

- 63).The polèng bang bintulu is the well-know diamond-patterned cloth each of whose panes should have one of the five magic colors. Chandrakirana is, as is known, a name for the princess of Daha, wife of Panji. I do not know why Bima’s armband bears this name. Nagasara (1,000 snakes) or nagabanda (snake-band) indictes Bima’s snake upawita. The jarot-ing-asĕm(the rib of a tamarinde pod) is the sharp-pointed ear ornament of Bima.Google Scholar

- 64).Here as well as in version B we have, in the words of Rouffaer, something very important, viz., that Bima here becomes identified with Gaṇeça (Gajahséna) ; this is again something entirely outside the ancient concept of Bhīma’s relationship with Wāyu, but more closely akin to the correlation Bhīma-Çiwa. The fact that our hero is identified with Gaṇeça is not as strange as it appears, since the latter is especially known as the remover of all obstacles, something which is equally true of Bima. As is known, both have the nāgopawīta. It would be interesting to determine where else this identification can be found. In his book about the wayang purwa Kats says at p. 255 that the “elephant Sena” (of a filial relationship to Guru no mention is made) is sent by Guru, breaks the caul and then “disappears like the wind”. If we are to consider this as meaning a rapid disappearance, then it has no significance in our case; if it is a less fortunate expression of “to disappear into nothing,” than one may speak of an identification. Cohen Stuart, I : XII, note 22, does speak of Gajahséna as Guru’s son, but not of a rebirth as Bima.Google Scholar

- 65).= Hastināpura.Google Scholar

- 66).These efforts refer to the countless magic devices to bring about pregnancy. These are never omitted, even when there is not the slightest indication that such would not occur.Google Scholar

- 67).Magic water with a potency to turn children immediately into grown ups. Almost all legendary heroes having become grown up by this water perform miraculous feats immediately after birth.Google Scholar

- 68).The name Sindurĕja (Sindhurāja) indicates that the word kĕling in the name of the realm of Banakĕling (Wana-kalingga) must indeed be held to indicate India.Google Scholar

- 69).Although Bima saw light later than Arjuna, yet he was born earlier and thus older.Google Scholar

- 70).Elsewhere Krĕndawahana. Krom Khāṇḍawa-wana ; the forest in Kuru-kṣétra?Google Scholar

- 71).= Wyāsa. Déwanata (dewanātha, king of the gods) stands for Pāṇḍu.Google Scholar

- 72).From Gajāhwaya, nickname of Hastināpura, which in the lakons however, represents the realm of the Pāṇḍawas.Google Scholar

- 73).= Duryodhana.Google Scholar

- 74).= Urnā.Google Scholar

- 75).Here we find an echo of the story about Umā’s adultery in Tantu Pang-gĕlaran and Sudamala (ed. Pigeaud, pp. 77, 146, and ed. Callenfels, pp. 10, 84). It is interesting to note that the reason given for the curse is the birth of Gaṇeça. It remains a question whether a connection may be assumed here with the Tantu passage where Urnā advises one of her sons born in adultery (Kumārasiddhi) to go and serve Gaṇa (= Gaṇeça). Her order to instruct human beings in the alphabet may also relate to Gaṇeça. The same applies to his other name: ĕmpu bhujāngga.Google Scholar

- 76).= Vessel of death; it remains a question whether it bears any relation to amṛtakuṇḍa, vessel with the elixer of immortality.Google Scholar

- 77).From tīrthakamaṇḍalu == urn with holy water. Confused with amṛta = water of life.Google Scholar

- 78).Here Batari Durga is not the same goddess as Dèwi Umayi; as is known, Durgā in the ancient sources is Umā, turned demonic by a curse.Google Scholar

- 79).= Wasudewa (Kṛṣṇa’s father) of Mathurā on the Yamunā.Google Scholar

- 80).Elsewhere nalibrata or nalibrangta. Is this connected with the abstinence of Kuṇṭī? (narī and wrata).Google Scholar

- 81).= Mādrī.Google Scholar

- 82).Yudhiṣṭhira.Google Scholar

- 83).This is the king of Banakĕling (Sapwani) of the previous version, who by taking to the air has indicated that he is also Bĕgawan, a holy man. Here, however, the story deviates sharply from the other version.Google Scholar

- 84).= Widura.Google Scholar

- 85).Elsewhere Domya, from the Sanskrit Dhaumya, younger brother of Dewala and housepriest of the Pāṇḍawa.Google Scholar

- 86).In the Mahābhārata not the name of Indra’s heaven, but of a city of the Kīcakas. A possible confusion with cakra?Google Scholar

- 87).= Indrakīla.Google Scholar

- 88).According to others a son of Yamadipati (Yama) inhabiting the Kilasa (= Kailāsa).Google Scholar

- 89).Elsewhere Ragu.Google Scholar

- 90).Probably this is another of the “deliverance episodes” of which a few appear on Sukuh reliefs. Brama and Bayu would thus have been transformed into butas pursuant to some curse or other and have regained their original features. Cf. the Sudamala, where the same thing happens to Durgā.Google Scholar

- 91).From smarakathā? Elsewhere, however, I have found smarachakra. Elsewhere smarakata is the name of the patih of the kingdom Ngargapura.Google Scholar

- 92).Unknown from other sources.Google Scholar

- 93).Patu and Temboro (elsewhere Tĕmburu) are lesser gods; the former is the confidant of Narada, the latter a gawdharwa. Tĕmboro from the Sanskrit Tumburu.Google Scholar

- 94).From the Sanskrit Rājendraçāstra or Indrārjaçāstra? In the first case the same as rājazvidyā or rājaçāstra, knowledge (book of learning) of the kings.Google Scholar

- 95).It is to be noted that unlike in the Mahābhārata Pāṇḍu does not shoot the animals whilst engaged in their love affair in the forest. Similarly, nothing remains of the curse uttered by the wounded ṛṣi against Pāṇḍu pursuant to which the latter will die while making love. The only trace left of this is Pāṇḍu’s feeling of oncoming illness after the affair with the kidangs. An instructive passage on the origin of differing versions of the stories!Google Scholar

- 96).Javanese kanching gĕlung, the hair clasp; in the case of Brataséna the garuda mungkur. Although as Werkodara Bima has no garuda mungkur, the term nevertheless remained in use here.Google Scholar

- 97).Originally they clung to the ends of the dodot ; in the paḍalangan, however, the word porong is used; this refers to the naga knobs put on Bima’s pants — with which he was outfitted after Kartasura — supposedly as a memento of his fight with the nagas in the Bimasuchi.Google Scholar

- 98).The wot ogal-agil corresponds to the Balinese titi gong gang, the bamboo bridge in front of the pura-gate, used in administering the oath and undoubtedly a replica of the bridge of souls in front of the entrance to the home of the souls (see Korn, Adatrecht van Bali, II, p. 361). Only in the mountain villages such bridges are still found; they are undoubtedly of ancient native origin. The séla matangkĕp are the rocks standing to the left and right of the entrance to the abode of the souls (heaven). They collapse when an ineligible soul attempts to pass. They are the heavenly prototype of the chandi bĕntar of the Balinese pura’s.Google Scholar

- 99).The picture of hell here is clearly that of a volcano located in heaven and differs strongly from the Hindu idea. One may imagine the scene of these events being like the Diëng plateau. Elsewhere (TBG, LXXIV, p. 284) I have identified the Diëng plateau as the place where according to ancient Javanese legend Pāṇḍu was “interred”, i.e. acquired his place in heaven (see above, scene ten) called Çataçṛngga (Saptarĕngga).Google Scholar

- 100).Here, one will have to imagine a terraced sanctuary like the one at Sukuh or, more clearly still, like one at Chĕṭa. The meaning of the number 29 escapes me here. Chĕṭa has only fourteen steps (according to the counting by Van der Vlis), although there may have been more originally. In Bali the highest holy number is 13.Google Scholar

- 101).A tube made of strips of bamboo.Google Scholar

- 102).Yamunā, a tributary of the Ganges.Google Scholar

- 103).Cf. Poerbatjaraka in Agastya p. 19, where the further adventures of the tala oil are related. In the episode of the battle with the Korawa the influence of the Garuḍeya is in my opinion not to be denied.Google Scholar

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-94-017-5987-8_4

Keris Relief (Blacksmith Relief)

[quote]The scene in the bas relief depicts Bhima as the Blacksmith in the left forging the Metal - a Kris ; he extends its blade into the fire. A tier of three shelves above his left shoulder illustrate (1) the tools of his trade (bottom shelf: a file, hammer, etc.) (2) the weaponry he produces (middle shelf: a knife, etc.) and (3) the ceremonial objects he produces (top shelf: finials) , Ganesha in the center dances upon a platform while holding a dog , and Arjuna in the right operating the tube blower to pump air into the furnace pump that extend , along the bottom of the relief, to the forge in the left hand panel. The relief is highly celebrated, and has been exhibited abroad.

Keris Relief (Blacksmith Relief)

The wall of the main monument has a relief portraying two men forging a weapon in a Smithy with a dancing figure of Ganesha, the most important Tantric deity, having a human body and the head of an elephant. In Hindu-Java Mythology, the Smith is thought to possess not only the skill to alter metals, but also the key to spiritual transcendence. Smiths drew their powers to forge a kris from the god of fire; and a Smithy is considered as a Shrine. Hindu-Javanese Kingship was sometimes legitimated and empowered by the possession of a kris.

The elephant head figure with a crown in the Smithy relief depicts Ganesha, the God who removes obstacles in Hinduism. The Ganesha figure, however, differs in some small respects with other usual depictions. Instead of sitting, the Ganesha figure in Candi Sukuh's relief is shown dancing and it has distinctive features including the EXPOSED GENITALIA, the demonic physiognomy, the strangely awkward dancing posture, the rosary bones on its neck and holding a small animal, probably a dog.

The Ganesha relief in Candi Sukuh has a similarity with the Tantric ritual found in the history of Buddhism in Tibet written by Taranatha.[5] The Tantric ritual is associated with several figures, one of whom is described as the "King of Dogs" (Sanskrit: Kukuraja), who taught his disciples by day, and by night performed Ganacakra in a burial ground or charnel ground.

The forging of iron, and in particular of the iron knife-blades known as Kris, or Keris, had a Spiritual Significance in Indonesia that is comparable to the special importance of sword-making in Japan. The Indonesian iron-worker was allocated to a special caste, that stood outside the typical Hindu caste system and did not necessarily yield, in precedence, even to Brahmins.[unquote]

Bhima. Wayang Kulit Klasik.

Bhima. Wayang Kulit Klasik.

Bhima. Candi Sukuh. Indonesia. Bhima Relief In Wayang Style - A Carving Depicting A Womb with Mythological Creatures. "The subject of this relief is Bhima, a hero of the Mahabharata, posed opposite a God on pedestal within a horseshoe-shaped arch. The sides of the arch are formed by the exaggerated tails of two birds, whose heads and bodies appear below the relief. A kala-like ogre is placed at the top, between two more ogre faces at the tips of the birds' tails. The central figures are sculpted in Wayang Puppet style, and indeed resemble their leather-puppet counterparts in posture, costume, and sideways presentation. A triad of indistinct figures appears below, in the narrow neck of the arch; the upper figure of the triad supports a Shrine or pavilion on his upraised hand, while the bottom two figures appear to Pass something between them."

Bhima Overcomes A Foe "These reliefs show Bhima rushing into battle, with bow and spear. He is preceded by a smaller standard-bearer, whose flag is emblazoned with Bhima's image; appropriately, since Bhima was of course the general of his troops. The hero's curling hair is distinctive, and appears on both images of him.

In this relief, mighty Bhima (identified by his curled hair, as on the previous page) lifts a foe off the ground by the sheer strength of his arm. Behind the hero is one of his followers, a soldier equipped with shield and spear. An inscription above Bhima's head tells the story."

Some other reliefs depicting story of Mahabharata - Bhima

Headless Statue of Bima

Stone inscription.

Some more Reliefs depicting Life of Bima

Bhima (Bima), second of the Pandava (Pandawa) brothers, approx. 1960. Indonesia; West Java. Wood, cloth, and mixed media. From the Mimi and John Herbert Collection, F2000.86.157.

"Bhima (Bima) is the second of the Pandava (Pandawa) brothers in the Mahabharata, a great Hindu epic. He is the divine son of the wind god Vayu (Bayu), and is known for his military skill, physical power, bravery, and voracious appetite. Although Bhima has a tendency to demonstrate a lack of selfcontrol, his intentions are always honest and noble. While in exile because his brother Yudhishthira (Yudistira) has lost their kingdom in a gambling bet, Bhima marries the princess giant Hidhimba (Arimbi), with whom he has a son, who is named Ghatotkacha (Gatotkaca). Having descended from the wind god, Bhima has the ability to fly, as does his half-brother Hanuman (Hanoman) and his son Ghatotkacha.

In one story from the Mahabharata, the fierce warrior Bhima defeats a dragon, which then transforms itself into a poisonous serpent. Bhima wraps the serpent around his neck, declaring that it may bite him should he ever tell a lie."

Indonesia Bali Bhima Monument Kuta, Indonesia.

Stone Guradian Figure of Bhima, Majapahit Style, Indonesia. 15thC

Bhima. Sculpture. Ancol.Jakarta. Indonesia

"In the Mahābhārata, Bhima (Sanskrit: भीम, IAST: Bhīma, Tibetan: མི་འཇིགས་སྟན; Wylie: mi 'jigs stan) is one of the central characters of Mahabharata and the second of the Pandava brothers. Bhima was distinguished from his brothers by his great stature and strength.

His legendary prowess is celebrated in the epic: "Of all the wielders of the mace, there is none equal to Bhima; and there is none also who is so skillful a rider of elephants. In fight, they say, he yields not even to Arjuna; and as to might of arms, he is equal to ten thousand elephants. Well-trained and active, he who hath again been rendered bitterly hostile, would in anger consume the Dhritarashtra in no time. Always wrathful, and strong of arms, he is not capable of being subdued in battle by even Indra himself. Bhima a Maharati, capable of fighting 60,000 warriors at once, so mighty was he that when he were to roar in anger he would put to shame the proudest lion and frighten the most fearless warrior." en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhima

Bhima. Museum. Wayang.

Bhima Shakti sculpture in Bali, Indonesia (L) and a statue of Hanuman (R). Pic courtesy: Thinkstock Photos

Mumbai: Bhima, the strongest of all the Pandavas, who along with his brothers was responsible for uprooting the existence of the Kauravas, was born to Kunti, the first wife of King Pandu.

But he was born out of a boon to Kunti after she had invoked Vayu Devata. He wasn’t Pandu’s biological son.

Here’s the legend behind Bhima’s birth

King Pandu had unknowingly shot Rishi Kindama (in disguise as a male deer) with an arrow while the latter was engaged in lovemaking with a female deer. The Rishi had great inhibitions about making love in the presence of humans and to quench his sexual needs, he would transform into a deer with his special powers. Mistaking Rishi Kindama to be a deer, King Pandu shot him thereby injuring him seriously. Angered after being injured, Rishi Kindama curses the king by telling him that he would meet death if he ever tried to make love with a woman.

Saddened by the curse, Pandu, who wishes to have children, reminded his first wife Kunti to use the boons granted to her by Rishi Durvasa. Thus, Yudishthira was born to Kunti after she was blessed by Yama and then Vayu Devata blessed her with Bhima.

Bhima and Hanuman

Hanuman was born to Anjana after she was blessed by Lord Shiva. The Lord had asked Vayu Devata to bring a portion of the divine pudding that was being consumed by Dasharatha’s queens in Ayodhaya, for Anjana. After consuming the pudding, Anjana was blessed by Vayu and granted her wish to have a child. Since he was responsible for bringing the pudding, he was rightfully the father of Anjana’s child.

Since both Hanuman and Bhima were born after being blessed by Vayu, they were brothers.

Many of us are not familiar with Hidimbi, whose selflessness contributed a lot to the victory of the Pandavas against the Kauravas.

We often tend to remember only those characters that play lead characters thereby forgetting the significant roles played by the lesser known or popular ones. We all know Draupadi as the wife of the Pandava brothers, daughter of King Panchal and the soul-sister of Lord Krishna. But many of us are not familiar with Hidimbi, whose selflessness contributed a lot to the victory of the Pandavas against the Kauravas.

Who was Hidimbi?

Hidimbi was the sister of Hidimba, a rakshas.

How, when and where did she meet Bhima?

During their exile, the Pandavas dwelled in forests. One night, when the rest of the brothers were asleep, Bhima remained awake to keep a watch. On smelling the presence of humans around, Hidimba asked his sister Hidimbi to lure Bhima and convince him to get eaten by them. Hidimbi met Bhima in disguise of a beautiful woman and instantly fell in love with him. And hence she confessed to him about her real identity.

Bhima, known for his strength and valour, refused to pardon Hidimba. The two indulged in a fight that resulted in Bhima’s victory. With Hidimba’s death, Hidimbi was orphaned. She pleaded to Bhima to marry her because she had fallen in love with him. After initially declining her proposal, Bhima married her after being asked by his mother Kunti but on one condition. He told her that he would not be able to take her to along with him after his exile period ends. She agreed to it gladly. Within a year, Hidimbi bore a son for Bhima and named him Ghatotkacha.

Ghatotkacha was raised by his mother and was later a part of the battle of Kurukshetra where he stood by his father against the Kauravas.

Her selfless contribution

Hidimbi could have been the queen of Hastinapur by virtue of her marriage to Bhima. But she chose to live in the forests and raise her son Ghatotkacha single-handedly. It was no petty sacrifice. Despite being a married woman, she lived without her husband because of the condition put forth by him. However, according to another legend Hidimbi chose to live alone to do penance.

Hidimba Devi Temple, North-east View

Hidimba Devi Temple (built 1553 onward)

Hidimba Devi temple stands in the midst of a sacred cedar forest near the town of Dunghri at the verdant foot of the Himalaya mountains. The sanctuary is built over an enormous rock that juts out of the ground, worshipped as a manefestation of Durga, the "Hill Mother" or goddess of the earth. The temple was constructed in 1553 by Maharaja Bahadur Singh, who made a promise to the Hidimba deity of the Mahabharata epic.

The temple is rather unusual and is architecturally similar only to the temple of Tripura Sundari in Naggar (also in the Kulu valley). The Hidimba Devi temple is 24 meters tall and consists of three square roofs clad in timber tiles, surmounted by a cone-shaped fourth roof that is covered in brass. The interior of the temple is occupied by the large rock and contains no usuable space except for the ground floor. Curiously, a rope dangles from the ridge that is said to have been used to hang victims by the hand, who were then swung—bleeding and bruised—over the large rock in the presence of the goddess.

The base of the temple is made of whitewashed mud-covered stonework. The main doorway includes an elaborately carved wooden entrance that is believed to be over 400 years old. These and other carvings center on the goddess Durgha who is a mainstay of pan-Indian stories. However, the goddess herself is represented only once in a three inch tall brass image.

During the Pandava's exile, when they visited Manali; Bhima, one of the five Pandavas, killed Hidimb. Thereafter, Hidimba married Bhima and gave birth to their son Ghatotkacha. The Hidimba Devi Temple has intricately carved wooden doors and a 24 meters tall wooden "shikhar" or tower above the sanctuary.[2] The tower consists of three square roofs covered with timber tiles and a fourth brass cone-shaped roof at the top. The earth goddess Durgaforms the theme of the main door carvings.[3] The temple base is made out of whitewashed, mud-covered stonework. An enormous rock occupies the inside of the temple, only a 7.5 cm (3 inch) tall brass image representing goddess Hidimba Devi. A rope hangs down in front of the rock,and according to a legend,in bygone days religious zealots would tie the hands of "sinners" by the rope and then swing them against the rock.[4]

About seventy metres away from the temple, there is a shrine dedicated to Goddess Hidimba's son, Ghatotkacha, who was born after she married Bhima...

The Indian epic Mahabharata narrates that the Pāndavas stayed in Himachal during their exile. In Manali, the strongest person there, named Hidimba and brother of Hidimdi, attacked them, and in the ensuing fight Bhima, strongest amongst the Pandavas, killed him. Bhima and Hidimba's sister, Hidimbi, then got married and had a son, Ghatotkacha, (who later proved to be a great warrior in the war against Kauravas). When Bhima and his brothers returned from exile, Hidimbi did not accompany him, but stayed back and did tapasyā (a combination of meditation, prayer, and penance) so as to eventually attain the status of a goddess.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hidimba_Devi_Temple

A mughal depiction of Ghatotkacha (top) getting killed by Karna (top left). Ghatotkacha , is a character in the Mahābhārata epic and the son of Bhima and the giantess Hidimbi (sister of Hidimba). His maternal parentage made him half-Rakshasa (giant), and gave him many magical powers.

Bhimsen and Ghatotkacha http://openlibrary.org/books/OL23365037M/Mahabharata.

Ghatotkacha (Sanskrit: घटोत्कच Ghaṭōtkaca "Bald Pot") is an important character in the Mahabharata.His name comes from his head, which was hairless (utkaca) and shaped like a ghatam. Ghatotkacha was the son of the Pandava Bhima and the Rakshasi Hidimbi. His maternal parentage made him half-Rakshasa and gave him many magical powers such as the ability to fly, to increase or decrease his size and to become invisible. He was an important fighter from the Pandava side in the Kurukshetra war.

Ghatotkacha was born to Hidimbi and the Pandava Bhima. When traveling the countryside with his brothers and mother as a brahmin, having escaped the lakshagraha, Bhima saved Hidimbi from her wicked brother Hidimba. Soon after Ghatotkacha was born, Bhima had to leave his family, as he still had duties to complete at Hastinapura. Ghatotkacha grew up under the care of Hidimbi. One day he received a pearl which he later gave to his cousin Abhimanyu. Like his father Ghatotkacha primarily fought with the mace. Lord Krishna gave him a boon that no one in the world would be able to match his sorcery skills (except Krishna himself).His wife was Ahilawati and his sons were Barbarika and Meghvarna.

Ghatotkacha (Sanskrit: घटोत्कच Ghaṭōtkaca "Bald Pot") is an important character in the Mahabharata.His name comes from his head, which was hairless (utkaca) and shaped like a ghatam. Ghatotkacha was the son of the Pandava Bhima and the Rakshasi Hidimbi. His maternal parentage made him half-Rakshasa and gave him many magical powers such as the ability to fly, to increase or decrease his size and to become invisible. He was an important fighter from the Pandava side in the Kurukshetra war.

Ghatotkacha was born to Hidimbi and the Pandava Bhima. When traveling the countryside with his brothers and mother as a brahmin, having escaped the lakshagraha, Bhima saved Hidimbi from her wicked brother Hidimba. Soon after Ghatotkacha was born, Bhima had to leave his family, as he still had duties to complete at Hastinapura. Ghatotkacha grew up under the care of Hidimbi. One day he received a pearl which he later gave to his cousin Abhimanyu. Like his father Ghatotkacha primarily fought with the mace. Lord Krishna gave him a boon that no one in the world would be able to match his sorcery skills (except Krishna himself).His wife was Ahilawati and his sons were Barbarika and Meghvarna.

In the Mahābhārata, Ghatotkacha was summoned by Bhima to fight on the Pandava side in the Kurukshetra battle. Invoking his magical powers, he wrought great havoc in the Kaurava army. In particular, after the death of Jayadratha on the fourteenth day of battle, when the battle continued on past sunset, his powers were at their most effective.

At this point in the battle, the Kaurava leader Duryodhana appealed to Karna, to kill Ghatotkacha as the whole Kaurava army was coming close to annihilation due to Ghatotkacha's attacks. Karna possessed a divine weapon called the Vasavi Shakti, granted by the god Indra. Only able to use it once, Karna had been saving it for his battle with his rival, Arjuna. Unable to refuse Duryodhana, Karna discharged the weapon against Ghatotkacha, killing him. It is said that when Ghatotkacha realized that he was going to die, that he assumed a gigantic size. When the huge body fell, it crushed one akshauhini of the Kaurava army.[5] After his death Krishna was glad Karna no longer had Vasavi Sakthi to use against Arjuna.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghatotkacha

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Def9PhrdMXs Published on Jun 9, 2015

Lord Hanuman was born in Jharkhand’s most forested area 20 ms away from Gumla district in Aanjandham.

Comments